This article first appeared on DUSA Media.

In a long piece over at the University of Birmingham’s “Redbrick”, Laura Brindley describes this theoretical scenario:

A fourteen year old girl has been violently gang raped by five men, in littered woods, just ten minutes away from where the girl lives in her council flat with her single mother and four siblings. On a humid summer night, a girl drunk with cheap vodka the men had bought her loses her childhood … [T]he girl has a “bad girl” reputation in school.

The defense uses the girl’s reputation against her in court, and her rapists go free.

In her headline, Laura asks whether you can morally defend a rapist. She argues that defense lawyers “who know deep down that their client is guilty of rape (whether the client had said the words out loud or not)” should “put forward the truth whether it loses them their case or not.” I think it’s the wrong question to ask, and the way she goes about answering it misunderstands both the job of the justice system and role of the various parties in it.

In Laura’s scenario, there’s no question that the girl was raped. In real life, however, this case would start with a claim by a girl, and whether or not her story is true needs to be investigated. When Philip Rumney reviewed studies on the subject in 2006, he found that false reporting rate estimates ranged from 1.5 percent to 90 percent (ungated copy here). Recent estimates tend to be on the lower end. A March 2013 report by the Crown Prosecution Service, for example, said that between January 2011 and May 2012, there were 5,651 prosecutions for rape in England and Wales, compared to 35 prosecutions for making false allegations to that effect. (That number doesn’t include withdrawn allegations.)

Let’s be clear: False rape allegations are rare. But that doesn’t mean that the number of allegations automatically equals the number of crimes. (Unfortunately, that’s true both ways: Too many rapes aren’t reported because many victim are too afraid or too ashamed.) And given that it’s almost impossible to navigate the spider web of laws and precedents without expert help, defendants only have a chance to prove their innocence with the help of a lawyer.

In a trial, there are three parties, and each has a distinct role. Put simply, the prosecution assumes the very worst about the defendant and presents the evidence that backs up its case. The defense assumes the very worst about the victim and presents the evidence that backs up its case (or plays devil’s advocate and attempts to weaken the prosecution’s version of events). Judges and juries look at the evidence and have to figure out which side’s version is closer to the truth. This process often results in verdicts that the public finds frustrating or disappointing.

An emotional response to some verdicts isn’t a good reason to abandon a pretty well tested system, though. Each side deserves to be heard and has the right to question the other side’s version of events. Again, only in the scenario can we know for sure that the rape happened; in real life, we’d probably have two conflicting versions of what happened, and at least initially no way of knowing for sure which one is true.

Laura’s alternative would seriously undermine that balance. Let me quote her again, because I don’t want to mischaracterize her position (emphasis mine):

The problem are defence lawyers who know deep down that their client is guilty of rape (whether the client had said the words out loud or not) … We need more defence lawyers who are prepared to find out the real story from their client and put forward the truth whether it loses them their case or not.

According to Laura, it doesn’t require the defendant’s admission for the defense to effectively switch sides. I assume that by “deep down”, Laura actually means “after careful examination of the available evidence;” everything else would be fairly indefensible. But every trial already has a party whose job it is to weigh the evidence and attempt to reach a verdict informed by the facts: judges and juries. They determine whose version is more credible after both sides get to question each other’s stories, but for that they need to hear both sides. They’d only get to hear one if defense lawyers followed Laura’s suggestion.

There certainly are defense teams who aggressively portray their opponents as unreliable. But experience tells us that in Laura’s scenario, the prosecution would probably try the same. What if one of the alleged rapists had been accused of domestic violence by an angry ex-wife in the past, even if the case was dismissed? Or another had been a former alcoholic who had been unemployed for years and was suffering from depression as a result? It doesn’t take much imagination to see these circumstances being brought up by the prosecution (or being leaked to willing “journalists” eager for a “scoop”). It’s a dirty game both sides routinely play, and the effects probably cancel each other out.

The question is not whether it’s immoral to defend a rapist, but for the record, it’s not. In our judicial system, loyal and competent defense lawyers are a prerequisite for a fair trial. In dubio pro reo and the presumption of innocence until proven guilty are two pillars of the rule of law. Both put the burden on the prosecution, and for good reasons. In some cases, that may result in an acquittal because there isn’t enough evidence for the prosecution to prove their case.

On a personal level, that may be tragic. But for a society, having some who are guilty go free is a smaller price to pay than putting many who are innocent behind bars.

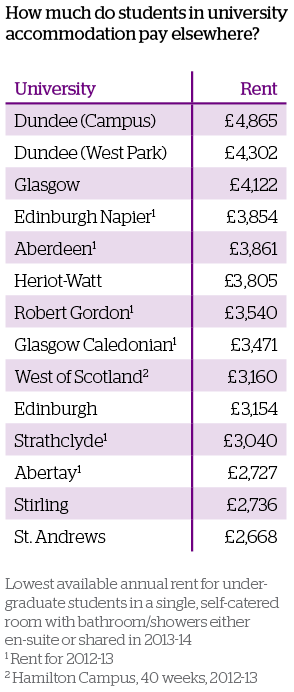

No other University in Scotland charges more than Dundee for a self-catered single room. Rents in University residences in Edinburgh and Glasgow are significantly lower, despite higher average rents for one-bedroom properties in both cities. Even in “posh” St. Andrews, students who are fine with walking 15 minutes to the city centre can live in much more affordable accommodation.

No other University in Scotland charges more than Dundee for a self-catered single room. Rents in University residences in Edinburgh and Glasgow are significantly lower, despite higher average rents for one-bedroom properties in both cities. Even in “posh” St. Andrews, students who are fine with walking 15 minutes to the city centre can live in much more affordable accommodation.